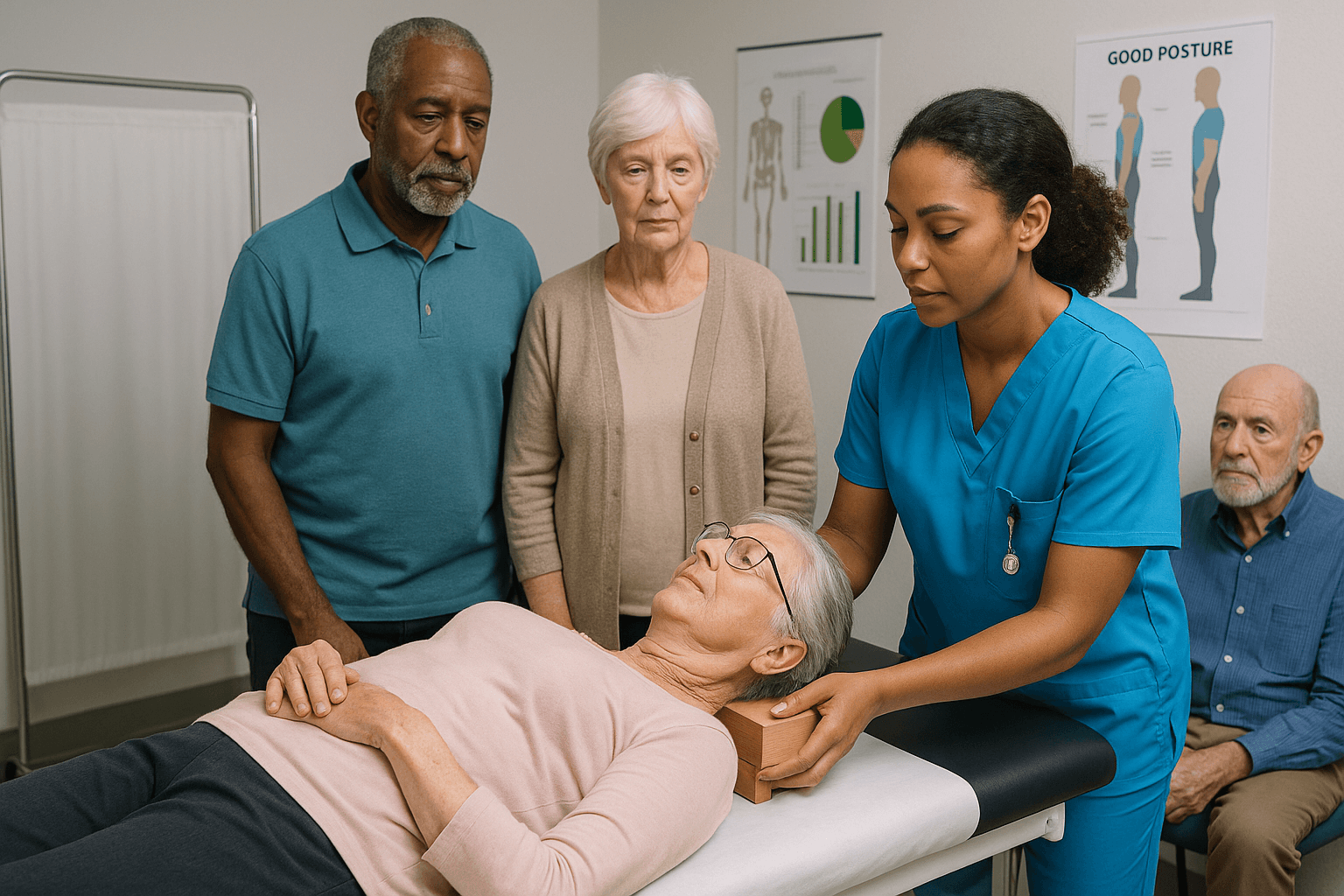

If you ever try to lie flat on your back and need to prop a pillow or a stack of blocks under your head, you may be displaying hyperkyphosis—a forward‑bending curve of the upper spine. Most people think a hunch is merely cosmetic, but a 2006 study of community‑dwelling women from the Rancho Bernardo cohort shows that even a modest curve can raise the chance of a bone fracture, independent of bone density or past injuries.

Jump to:

- TLDR – Quick Guide

- Who Was Studied?

- Measuring “How Much Hunch?”

- What Else Was Recorded?

- Core Research Question

- Main Results (Plain‑Language Summary)

- Why Might a Forward Curve Increase Fracture Risk?

- Strengths & Limitations

- Take‑Away Message for the General Reader

- Connecting the Science to Posture Improvement: Advanced BioStructural Correction (ABC)

- Key Takeaways

- FAQs

TLDR – Quick Guide

- Hyperkyphosis = forward curve of upper spine (even mild cases matter)

- Block test: needing ≥1 block = hyperkyphosis

- 1.7x higher fracture risk even after adjusting for age and bone density

- Severity matters: 3+ blocks = 2.6x risk of fractures

- 27% of women with hyperkyphosis had fractures vs. 16% with normal posture

- Common fracture sites: wrist (22%), hip (15%), spine (10%)

- Fracture risk not explained by falls or weak bones alone

- Simple posture test predicts long-term bone health risks

- ABC™ may help reduce hyperkyphosis and related fracture risk

Who Was Studied?

| Characteristic | Details |

| Population | 596 women, ages 47‑92 (mean ≈ 71) living in Rancho Bernardo, California |

| Time frame | Baseline measurements 1988‑1991; follow‑up for new fractures averaged 4 years |

| Why women only? | Men made up < 5 % of the original cohort, so the analysis focused on women |

Measuring “How Much Hunch?”

Researchers used a simple block test instead of sophisticated imaging:

- The participant lies on a DXA (bone‑density) scanner.

- If her head cannot stay flat, the examiner slides thin wooden blocks (each 1.7 cm thick) under the head until the head is level.

- The number of blocks needed becomes the kyphosis score.

- 0 blocks = normal posture.

- ≥ 1 block = hyperkyphotic posture.

In this group, 18 % (≈ 104 women) needed at least one block, with some requiring up to nine.

What Else Was Recorded?

- Bone mineral density (BMD) of hip and lumbar spine (DXA).

- History of prior fractures (any site).

- Lifestyle factors: smoking, alcohol use, regular physical activity, body‑mass index (BMI).

- Falls in the previous year (self‑reported).

All of these variables can influence fracture risk, so they were entered into statistical models.

Core Research Question

Does hyperkyphosis independently predict future fractures after accounting for bone density, prior fractures, and other risk factors?

Main Results (Plain‑Language Summary)

| Finding | Interpretation |

| 1.7‑fold higher odds of any new fracture for women with ≥ 1 block, after adjusting for age and prior fractures (OR = 1.74, 95 % CI 1.02‑2.98). | A modest forward curve roughly doubles the chance of breaking a bone over the next four years. |

| Adjusting for BMD (spine or hip) barely altered the odds (still ~1.7‑fold). | The extra risk isn’t simply because these women have weaker bones. |

| Trend with more blocks: odds rose from 1.5 (one block) to 2.6 (three or more blocks). | The more pronounced the hunch, the steeper the fracture risk. |

| Falls did not explain the link. Adding a history of falls left the odds essentially unchanged. | The hunch appears to affect fracture risk through mechanisms other than just causing more falls. |

Numbers in Everyday Terms

- 107 women reported a new fracture during follow‑up (≈ 18 % of the whole cohort).

- Among those with hyperkyphosis, ≈ 27 % fractured, versus ≈ 16 % of women with normal posture.

- The most common new fractures were hip (15 %), wrist (22 %), spine (10 %), and a mix of “other” sites (rib, pelvis, ankle, etc.).

Why Might a Forward Curve Increase Fracture Risk?

- Marker of Underlying Osteoporosis – Prior work shows people with a hunch often have lower BMD. Even after statistically removing the BMD effect, the association persisted, suggesting the curve captures something beyond bone density alone.

- Altered Biomechanics & Balance – A slouched spine shifts the body’s center of gravity forward, potentially compromising stability. Yet, when researchers adjusted for reported falls, the risk stayed elevated, hinting that subtle changes in load distribution on the spine and hips may predispose bones to break even without a fall.

Strengths & Limitations

Strengths

- Large, community‑based sample (not limited to patients already seeking back‑pain care).

- Prospective design—measurements taken before fractures occurred, reducing recall bias.

- Simple, reproducible posture test that any clinic could adopt.

Limitations

- No baseline spinal X‑rays, so hidden vertebral fractures could not be fully excluded (they attempted to address this by later excluding participants with radiographic fractures).

- Self‑reported fractures for many sites (only hip, spine, wrist, clavicle were medically verified).

- Women only—findings may not apply to men.

- Falls were only captured at baseline; falls during the four‑year follow‑up were not recorded.

Take‑Away Message for the General Reader

Even a small, measurable forward bend—something you might notice when trying to lie flat on a table—can be a warning sign. It signals roughly a 70 % higher chance of breaking a bone over the next few years, independent of bone density or previous fractures. Spotting and addressing hyperkyphosis early could be an overlooked piece of the puzzle in keeping older adults fracture‑free.

Connecting the Science to Posture Improvement: Advanced BioStructural Correction (ABC)

The Advanced BioStructural Correction (ABC™) method is a full‑body alignment correction system that “detects and corrects misalignments that the body cannot self‑correct because there is no muscle—or combination of muscles—that can pull in the needed direction”. Its core steps are:

- Comprehensive Assessment – Practitioners locate structural misalignments throughout the spine and pelvis, not just the obvious “hunch.”

- Targeted, gentle adjustments – Using precise pressure and guided movement, the therapist applies corrections that produce instant changes in alignment. Repeating these sessions leads to gradual, whole‑body realignment over time.

- Posture Correction – By restoring proper alignment, muscle leverage (strength) improves so that the body begins to maintain an upright, balanced posture without excessive muscular effort.

Applying ABC to someone with hyperkyphosis could reduce the number of blocks needed in the simple test, thereby lowering the biomechanical stresses that the 2006 study linked to higher fracture risk.

While the research did not evaluate interventions, the logical next step is to test whether correcting hyperkyphosis with ABC (or similar alignment‑focused therapies) translates into fewer fractures in longitudinal follow‑up.

Until such outcome data are available, integrating ABC into a broader bone‑health strategy—adequate calcium/vitamin D, weight‑bearing exercise, regular BMD checks, and fall‑prevention measures—offers a proactive way to address both posture and fracture prevention.

Key Takeaways

Slouching isn’t just bad form—it could be a structural warning your body is sending. This landmark study shows how posture problems like hyperkyphosis are predictive of future fractures, independent of traditional bone health indicators like BMD.

- Even a minor hunch (1 block) increased fracture risk by 70%.

- The more blocks required, the steeper the risk—up to 2.6x.

- Risk persists even after accounting for bone density, prior fractures, or falls.

- Hyperkyphosis could be a biomechanical marker of hidden instability, not just weak bones.

- Simple assessments like the “block test” can be done in almost any clinic.

- Therapies like ABC™ may help reverse postural misalignments before fractures occur.

In the battle against fractures, bone density isn’t the only metric that matters. Postural alignment—especially in the upper spine—can silently shape your future health. Clinics like Upright Posture offer proactive solutions that address structure before symptoms become serious.

FAQs

1. Can hyperkyphosis develop without osteoporosis?

Yes, hyperkyphosis can occur even in people with normal bone density. The curvature is influenced by structural misalignments, muscular imbalances, and lifestyle factors like sedentary habits. It’s not always linked to osteoporosis, but it may signal underlying biomechanical stress.

2. How can I know if I have hyperkyphosis without seeing a doctor?

Try lying flat on a firm surface without a pillow—if your head doesn’t touch the ground comfortably, you might have mild hyperkyphosis. This quick self-check mimics the “block test” used in research settings. However, a professional assessment offers more precise insights.

3. What does Advanced BioStructural Correction™ feel like during treatment?

Most patients describe it as a series of gentle, guided movements that instantly improve posture. Unlike typical chiropractic methods, ABC focuses on structural corrections that the body can’t fix on its own. Sessions often result in noticeable changes even after one visit.

4. Is hyperkyphosis only a concern for older adults?

While the study focused on older women, hyperkyphosis can affect younger adults due to tech posture, injury, or structural imbalances. Addressing it early may prevent long-term issues like fractures or chronic pain. It’s a growing concern in today’s screen-heavy lifestyle.

5. Are there exercises to fix hyperkyphosis at home?

Some stretches and posture drills can help, but they rarely correct deep structural misalignments. Think of them more as maintenance than cure. Combining exercises with a structural correction approach like ABC™ often yields better, lasting results.